From Spain to Morocco, Benjamin-Constant in His Time

January 31 to May 31, 2015

Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal

The exhibition reveals six iconic aspects of Orientalism, offering a dual reading of its fictional subjects, juxtaposing staged pictorial settings with documented realities. Drawings and photographs round out this exploration of Moorish Spain and sharifian Morocco, between seductive mirages and the hidden realities of a colonial republic.

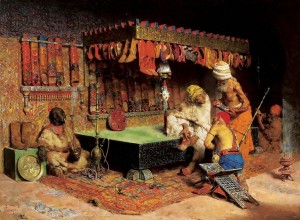

The Strategies of the Orientalist Studio

As an inescapable subject for literature and painting in the nineteenth century, the studio became a venue for fashionable receptions and a sales gallery for the painter. Visits were made by appointment.

Benjamin-Constant, the dandy and celebrated artist, elegantly monocled, hosted the cream of the European aristocracy to carry out business transactions amid an impressive clutter of mysterious and magically shimmering Oriental objects: multicoloured rugs, stuffed animals, inlaid suits of armour.

In the course of the century, the painter’s studio, an alternative to the official exhibitions of the Salon and widely reproduced in prints and photographs, became a fixed image in the public imagination. Its theatrical staging, the exoticism of the bazaar combined with the reality of souvenirs, constituted for the artist a showcase as much as a locus for inspiration, a studio designed to be toured.

From Delacroix to Gérôme, the studio became the decor. Rather than a secret laboratory for creation like Rodin’s workshop, it was to become the microcosm for receptions orchestrated by artists like Van Dongen and Warhol in the twentieth century.

The Salon, the Near East in History

“The Salon is our only means of dissemination. Through it, we achieve honour, glory and money. For many of us, it is our livelihood,” wrote Benjamin-Constant.

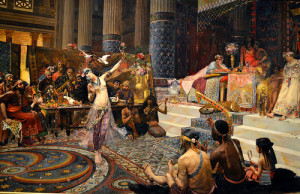

For a young history painter, a rite of passage in getting oneself noticed was to present at the Salon a “grande machine,” a tour de force piece that would attract attention in an exhibition crammed with thousands of canvases. As a result, confusion reigned between history painting in the grand style and large sensationalist canvases.

Benjamin-Constant was soon able to earn his living by selling works to the State. The exhibition displays several of these monumental canvases, restored and lent especially for this occasion. The leading light of the circle of Toulousian painters in Paris was Jean-Paul Laurens. A prime mover behind the revival of history painting under the Third Republic, Laurens specialized in exotic, even barbarous, at times macabre episodes from the Byzantine and Medieval periods.

His erudition, magnified by monumental settings, favoured scenes before or after the main action took place, suspended moments of tension or meditation. Benjamin-Constant admired his personal vision of the tragedies of history, depicting a picturesque brutality yet possessing great substance.

The Alhambra, Antechamber to the Near East

Until the Romantic era, Spain counted for little in the European imagination. However, this antechamber to the Near East became an indispensable destination with the rediscovery of Andalusia and its rich Hispano-Moorish heritage.

The Spanish painter Mariano Fortuny, an enthusiastic collector of Islamic art, set up his studio there and was joined by other artists who were passing through, including his friends Regnault, Clairin and Benjamin-Constant. Fascinated by the decorative abundance of polychrome stucco and also by the Romantic stories of Washington Irving and Chateaubriand, they executed dazzling and sanguinary paintings.

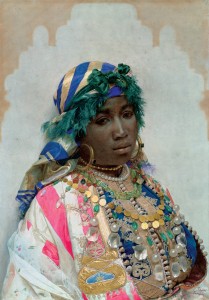

Tangier, the Charm of the “White City”

Only a few kilometres from Spain, from which it is separated by the Strait of Gibraltar, Tangier was nicknamed the “City of Foreigners” because of its historic cosmopolitanism.

Tangier attracted an ever-growing number of international artists, from the pioneers Delacroix and Dehodencq to Matisse and the Canadian painter Morrice. Tapiro, Fortuny, Regnault and Clairin spent long periods there, as did Benjamin-Constant, enthralled by its famous white terraces, the trading in the souks, the traditional Kasbah, the architecture of the Great Mosque and the bustling street life of the medina.

Colonial Diplomacy in Morocco:

Delacroix vs. Benjamin-Constant

Morocco, the “farthest land of the setting sun,” unlike the other countries of the Maghreb, had preserved its political independence from the Ottoman influence. This self-governing kingdom resisted the struggles for power of the European nations, maintaining an ever more asymmetrical relationship with them. Ever since Bonaparte’s Egyptian campaign in 1798, France had pursued its expansionist dreams in the Near East, seizing Algeria, its first African colony, in 1830.

Exactly forty years had passed between the trips to Morocco of Delacroix (1832) and Benjamin-Constant (1871-1873), both in the context of diplomatic missions: France wished to be sure of Morocco’s neutrality in regard to Algeria. This striking parallel between the two painters must be stressed.

Leaving Tangier, they found themselves in a land still dangerous for foreigners. Both were fascinated by its “barbaric” mores, its “theatre of cruelty” and its wild beauty, a savagery that was positively Medieval to their Eurocentric eyes: “Ah! Wretched people, what pain it gives to see your life, and what pleasure to paint it!” exclaimed Benjamin-Constant.

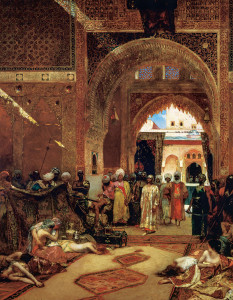

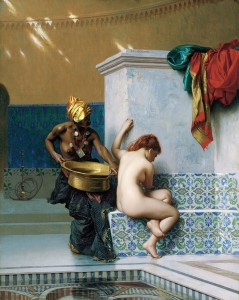

The Harem, Fantasies and Lies

The harem is a recurrent trope of Orientalist painting. In Arabic, haram, from which “harem” derives, refers to what is prohibited or sacred (as opposed to halal, denoting what is permitted or profane). It defined the space reserved for women in each household.

The object of endless curiosity and an incomparable source for fantasies, it was actually inaccessible to men, although Benjamin-Constant reported having crossed the threshold of some mysterious rooms in his Leaves from a Painter’s Note-book. For lack of suitable models in Paris, the artist executed in his studio numerous paintings, often monumental, of these exotic and sensual odalisques, acquiescent sex slaves subject to the pleasure of a decadent Oriental despotism – the Circassian whiteness of bewitching redheads, the servitude of black domestic slaves. The formula was successful!

The beautiful effects of the light piercing these secret interiors, shaded from the burning sun, dramatized the paintings. In France, as elsewhere, the salons were full of representations of languid nudes. This universal and reassuring acquiescence was not limited to Orientalist depictions, however, for when women began to assert their rights, their status stood as a threat to patriarchal society.

- Afternoon in the Harem, 1880.

- The Moroccan Caid Tahamy, 1883.

- The King of Morocco Leaving to Receive a European Ambassador, about 1885

- The Pink Flamingo, 1876.

- The Day after a Victory at the Alhambra, 1882

- Day of a Funeral Moroccan Scene, 1889

- Odalisque, about 1880

- Interior of a Harem in Morocco, 1878

- Tangerian Beauty, about 1891

- The Slipper Merchant, 1872

- The Massage, Hammam Scene, 1883

- Turkish Bath, also called Moorish Bath, 1870

- The White Slave, 1888

- The Death of Cleopatra, 1874

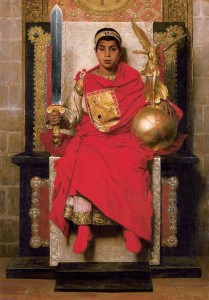

- The Late Empire: Honorius, 1880

- The Favourite of the Emir, about 1879

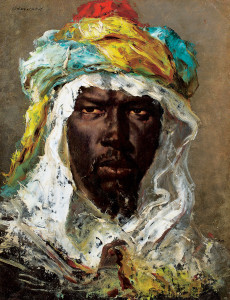

- Head of a Moor, about 1875

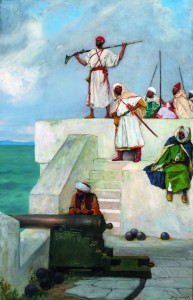

- The Pasha’s Soldiers, about 1889

- Salome Dancing for King Herod

- Evening on the Terrace (Morocco), 1879